My family was in the excavation business. When I turned 18, I started working excavation, literally in the trenches—installing sewer, water, storm drains, and utilities—everything underground. It was intense labor, but I loved it.

I worked my way up to where I operated different pieces of machinery, then took a position as foreman over my crew, and eventually managed all aspects of the jobsite from start to finish.

Instead of running the nicest piece of machinery—the most comfortable, cushy job—I took a different path. I put the most talented operator in that role, and I would set up the job to keep all obstacles out of the way and get decisions made, such as lining up the crew so they could focus on productivity. That protocol made my jobs some of the most profitable in the company.

I was always pulling high-profit margins out of my jobs because I discovered the best way to run them. In 2002, we did a job that had the highest performance I’d ever seen. We produced at an incredible rate because I learned to work with my crew and motivate them, giving them metrics like, “This is how much you accomplished yesterday. Let’s see if we can do more today.”

With this particular job, we had the surveyor come out and stake our sewer line. I called them two days later and said, “You need to come out and stake our water line” (the next task). They shot back with, “We just staked the sewer line two days ago.” I said, “Yeah, we’re done.” The surveyors said that was impossible, so they came out and verified we’d actually achieved as much work as we said we did. We were moving that fast.

When we got to the end of the job, the management of the company let me know we sucked. They told us we lost money, that the job didn’t go well, and that we didn’t perform well. I said that was impossible, and if that were true, it would not be possible to achieve profitability and we should get out of the industry.

I dug into the estimate. In construction, the estimator will size up the job and say, “This is what materials are required, here’s how much labor is required, and here’s how we’re going to do the job.” If the estimator makes a mistake, they’ve set the crew up for failure because they don’t have the ability to make a profit no matter how well they do. I suspected that was the case and dug into that estimate. I found out the estimator had completely missed items in the job.

Now, I wanted to start doing the estimating. I ran that position for a long time, learning to understanding the nuances that set the stage for success or failure. Eventually, I managed the whole company. As I took over the business, I started analyzing all the problems and challenges we experienced company-wide. I kept thinking, “There has to be a way to systematize all this because there are too many complications, and it’s too much for any one person to manage.”

That’s when I first had the vision for busybusy. One day in 2007, I was driving home and got an idea of how to solve all the problems I was dealing with. It was coming to me so fast. It was one of those inspirational moments where you have to capture it because if not, you’ll forget. I pulled over to the side of the road and started writing down all of the ideas, and as I was reviewing it, I thought, “This has to exist. There’s got to be this solution in the industry.” I wrote it all down, but I sat on it for a couple of years.

The Great Recession

Then it was 2008, and the Great Recession happened. Things got worse and worse for our excavation business. My wife and I didn’t have enough money and had to decide whether we were paying the credit cards or the mortgage, so we let the credit cards go. Then, as things got worse, it was, “Are we paying the mortgage, or are we paying for food and electricity?” So we let the mortgage go.

One day in July 2009, in my great desperation, I got down on my knees. I was praying and asking God, “I don’t know how I’m going to feed my family. I don’t know what I’m going to do.” The distinct impression I got back was, “You haven’t done anything with what I gave you.”

I finally got to work. I spent the next two years doing market research on the construction industry, validating my assumptions, and even doing it coast to coast. I hired a company out of Connecticut to do market validation research for me to ensure it wasn’t just Utah problems or geographical problems.

A lot of data came from the US Census Bureau. I found out that 70 percent of construction companies fail within seven years. If 100 companies go into business, seven years later, 30 of them would still be alive. It was like a survival island thing.

My nature is to dig for the root cause, so I started digging further. “What is the reason why these companies fail?” The best reasons I could find came from bonding companies. Bonding companies are insurance companies that will bond the performance of a job. For example, say a big government entity wants to do a project and the bonding company ensures the project is going to get done. No matter what, you can count on that road getting built because they put a performance bond on it.

Bonding companies have the best data because they do a lot of analysis to make sure they don’t lose the bond they’ve put up. It’s basically a guarantee that the project will be completed.

Everything pointed to the fact that contractors did not fail because they lacked the ability to do their skill set or trade labor. I couldn’t find any records of a bricklayer failing because he didn’t know how to lay bricks properly. All of the data pointed to companies failing because they have insufficient information to make proper and profitable decisions. They lacked knowing the business of running their business.

Contractors are typically like me. They come into the industry with a trade skill set, and when they become the owner or manager, they take on a whole new level of responsibilities that they have no skill set for—no skills in business management, customer management, asset management, regulations, etc.

Contractors have to manage a ton of responsibilities to stay in business. They end up being the best-skilled tradesmen in their field. They want to have more time and money, but they go into business for themselves and end up with less time and less money. Usually, their families suffer, and they often get divorced. They go from a really happy situation where they’re making pretty good money to deciding they want to work for themselves and pursue the American Dream—and that often feels like they wandered into hell.

My inspiration for busybusy was, “How do I solve those problems?” I had all the problems in my mind, from the personal side of business to how the subs interact with the general contractors, owners, architects, engineers, our suppliers, and our subcontractors. I had the vision for this whole network in my mind, but I didn’t know anything about technology—literally nothing.

I called a friend who had a computer science degree. My idea was a soup-to-nuts idea. It was like, “This is how we’re going to fix and change the entire construction industry.”

My friend said, “You don’t need me; you need a UX designer to start with, to wireframe your ideas, and to get through it.” This was in 2009, close to when the iPhone was introduced. If the construction industry knew what the iPhone would mean to them, they’d have rejoiced around the globe. No construction businesses had great data on themselves because it’s a mobile environment, and we never would without mobile technology.

In 2010, the UX designer I was working with introduced me to Dr. Eric Pedersen, the dean of the College of Science Engineering & Technology at Dixie State University. Eric loved that I wasn’t someone from the outside looking into the industry saying, “I can solve what I don’t know about.” I was from the industry and knew the solution.

Eric directed me to a programming team called Cabosoft. In 2010, mobile technology was very new, and he knew I needed it. Cabosoft had experience in developing apps. Our market research says we should develop for the BlackBerry because that’s what most contractors were using at the time, but Eric says, “No, BlackBerry is trending down. You need to develop for iPhone and Android only.”

Cabosoft began programming busybusy in December 2010, but it took us quite a number of years before we got to the point where we had anything we could sell. I had originally asked them how long they thought it was going to take, and they said about nine months. I was looking at about $100,000 in cost (of course, they didn’t comprehend the depth of my whole vision), but I made sure I had about $250,000 to start with. Of this whole industry-changing idea, there was this one button that had to collect the time it takes to do a job. Busybusy has now spent well over $25 million on that one button.I learned really quickly that I couldn’t swallow that whole elephant. I didn’t even know the size of the elephant I had outlined. I had to break it down to a bite. Over the course of those years, the more I comprehended what it would actually take to accomplish the job, the more I had to narrow it down to the most important thing: solving for the industry.

I picked time tracking because it was the hardest variable for contractors to understand. Labor data is the hardest to measure, with accuracy, in relation to the task a contractor is performing. They need to measure that against the time they estimated, and it’s hard to get that data with accuracy. Time tracking was the most important data to figure out so contractors could evaluate their labor cost at the end of the job and compare it to their estimate.

With the help of investors from the construction industry, the first busybusy app was launched in 2014 for various trades like landscaping, construction, excavation, painting, and plumbing jobsite intelligence. There have been many iterations since then, and today, busybusy collects data from the jobsite and brings it into business metrics—time data and resources like performance, photographs, notes, and reports—everything that comes from the jobsite.

Our goal is to inspire the behavior of employees to help them focus on revenue-producing activities. Let’s say you’re a roofer. You want to be the best you can be, and it’s not always clear what that means or how to get there. We want the software to inspire behavior to assist in maximizing the potential of workers because it also makes more money for them.

Most contractors make very little profit—maybe an average of 5 percent. That doesn’t mean there’s no profit to be made. I believe there’s up to 25 percent wasted in the industry due to inefficiencies.

The inspiration behind Tech Ridge

At busybusy, we thought, “When we get big enough, we’re going to develop our own campus like Google and provide all these amenities for our team members in the tech world similar to how the bigger tech companies do.” In 2016, the city of St. George, through Economic Development Director Matthew Loo, wanted to establish a tech center. The St. George economy was dominated by construction, healthcare, tourism, and education. They wanted to add tech to diversify the economy and create high-paying jobs.

The city was very smart about researching how to establish a tech center. They consulted with a guy out of Silicon Valley and asked him how to attract big tech companies to the local area. He said, “You don’t and you won’t.” He said Microsoft is in Seattle because Bill Gates lives in Seattle. Dell Computers is in Austin because Michael Dell went to the University of Austin. What the city had to do was find local tech entrepreneurs in St. George and see what they could do to help them build up their companies and stay in St. George. The city took that to heart. It was great advice.

The city reached out to Ryan Wedig (Vasion), Clint Reid (Zonos), and me. We didn’t know each other at time. They told us, “We want to create a tech center. Tell us what you need and what would help you the most.”

Ryan, Clint, and I needed the ability to attract and retain top talent. We asked ourselves, “How do we create an environment that helps us with that?” We agreed that if we aggregated the tech community, we could create synergies that could bring that future vision of campus amenities to the present day. This would also provide clear options for local graduates seeking jobs in the tech sector. If we all worked together, we could provide the same benefits to our people that Google or Facebook provide to theirs just by being aggregated and coming together as a community, which is a very St. George thing to do.

The position the city was in with companies like Vasion, Zonos, and busybusy was, “If they get big enough, they leave St. George because they can’t hire the talent they need here locally.” They would lose that tech industry over and over.

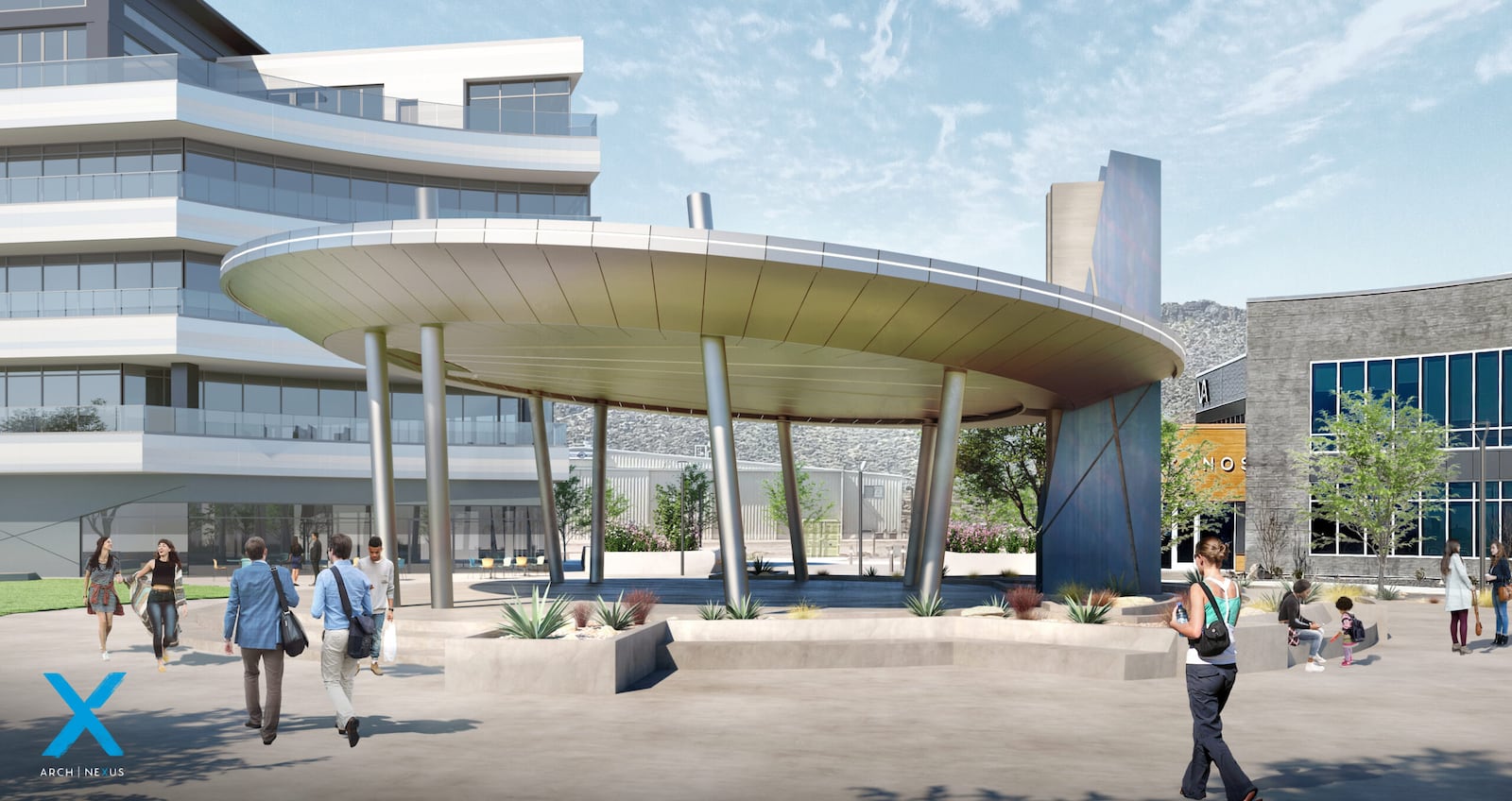

The city originally wanted us to just buy lots, but we said what we needed was a master-planned community with strong amenities. Because of my background in land development, I heavily advocated that this tech community needed to be planned out. We didn’t want to just come up here and start building—we needed to actually have a master plan. The city’s goal was to recruit and retain top tech companies, and our goal is to recruit and retain top talent. That objective is the North Star for Tech Ridge.

I had a good idea of how to get it done. My greatest talent is knowing how to hire the right people, and so I did.

The project relates exactly to our customer base at busybusy. I hired some of the best land planners in the nation, and they gathered in St. George and started working out the plan. We gave them our vision and they put together a land plan that focused on the “user” experience of being there.

The other huge benefit of Tech Ridge is the networking and collisions. For example, if one of my programmers is talking to one of Clint’s programmers, and they say, “I’m trying to solve this problem,” and Clint’s person says, “Well, I solved that a month ago,” they can help each other. That’s why there is more tech success in Silicon Valley.

Though rents and other costs are higher in Tech Ridge, it’s because of that network association where workers are able to associate with mentors that quickly tell them how to succeed and reduce the learning curve. Your chances of success are higher. The impetus behind Tech Ridge was creating a place that had a strong user experience for the talent.

Tech Ridge is now an economic juggernaut for the city of St. George. At full buildout, Tech Ridge adds $3.25 billion annually to the current GDP, increasing Washington County’s existing GDP by 50 percent.