Editor’s note: A previous version of this article stated that the demo automation market category was “measured at $73 billion in 2023, with a projected CAGR of 11.34 percent, projected to surge to $154 billion by 2031.” These numbers were updated May 22, 2025, to reflect more current market estimations.

Someone once asked me, “How do you define success?” I’ve always struggled to come up with a personal definition for this question, but what came out of my mouth surprised me: “Success is simply outlasting your failures.”

At the time, I was in between managing my first and second widespread layoffs at my startup, Consensus. I can only say “in between” in hindsight because you never plan to be in between layoffs. For a tech startup founder, layoffs are the organizational equivalent of going through medieval vivisection, where parts of the body are severed while the body is still alive. Letting perfectly productive, hard-working, intelligent people go is like losing a limb, eye or part of your brain. What’s left afterward is mangled and only partially useful, but still alive.

And that’s the point. Stay alive to fight another day, even if diminished and damaged.

Case in point: George Washington fought 17 battles during the American Revolution. He won only six but still won the war. He spent most of the war in a state of temporary failure, trying to stay alive to fight another day.

I believe the best and most enduring lessons are learned in failure, so I’ll share a few of the most significant in Consensus’ history thus far.

First, let me give you some context.

The origins of demo automation

In 2009, while I was running my previous software startup, there was a period when we were overwhelmed with leads. While that was a good problem to have, my small sales team could not keep up. I jumped in and started taking sales calls. One of the first things buyers want is a demo, so I also began doing a lot of demos. One day, I did six demos back-to-back and was exhausted. “These demos are a bottleneck. This is why sales can’t keep up,” I thought. That realization was the start of a journey that led to my involvement in creating a new category of demo automation software, a technology that automatically customizes a self-directed product demo for each buyer in the B2B buying group. In 2014, I designed and began to market a solution called DemoChimp.

The results have been astounding: Companies that employ demo automation have seen their close rates jump by more than 40 percent while simultaneously seeing their sales cycles shorten as much as 62 percent.

Later, I began to understand that the larger problem we were focusing on was not really about automation but fixing the broken process of buying enterprise software. Today, on average, more than 11 different stakeholders get involved in a purchase, making the buying process complex, painful and slow.

By making sure every stakeholder was able to get the customized demos they needed at different stages in the buying process, we helped the buying group avoid “group buying dysfunction” (the collective decision to do what is not in the best interest of the company because of group dynamics). I realized I was on to a new way of selling: focusing entirely on helping the buyer get past friction points in the buying process faster. This led me to both change the name of our company to Consensus and write a category-defining book about what I called “buyer enablement” titled “Selling is Hard. Buying is Harder.”

This and thousands of other contributions made by hundreds of Consensei (what we like to call our Consensus team members) have ultimately created a market category recently measured at $1.5 billion in 2024, with a projected CAGR of 16.3 percent, projected to surge to $5.4 billion by 2033.

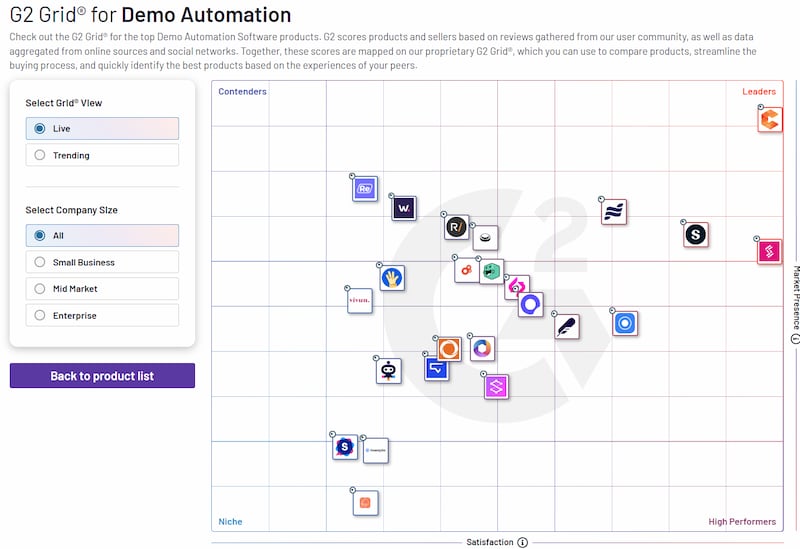

Consensus now boasts more than half of the world’s top 30 enterprise software companies as customers, including industry titans such as Salesforce, Sage, SAP, Oracle, Workday, Coupa and Atlassian. We are consistently rated as the unquestioned leader in the nascent Demo Automation market.

But all of this success was in the unseeable, unknowable future when I was “between layoffs” back in 2016. I dreamed of it, yes. Deep down, I believed in it (most of the time). But it seemed impossible after I had laid off more than half of my workforce, burned too much cash every month, and had a unit churn rate of nearly 50 percent.

Almost every technology startup success traverses a non-linear, somewhat chaotic path littered with detritus of failure after failure. So when people ask me how we succeeded, I can point them to several things that eventually worked, but the contributions to success are so varied, wide and deep that it’s impossible to point to just a few things and declare them the undeniable drivers that made us win.

But failures are easier to point to and perhaps more valuable to learn from. If you can avoid certain failures, you’ll be more likely to outlast the other future failures and eventually reach success.

Failure #1: Not validating long-term value creation and retention

In 2013, having just come off of a modest success with my previous technology startup, I was eager to put my hand to another project where I could improve on what I had learned. I wanted to make sure I got validation right before pressing the accelerator. When I showed pencil sketches of the first iteration of my demo automation software to friends and colleagues, the response was positive — but because these were all friendly acquaintances, I wasn’t sure I was getting the straight stuff from them.

At about that time, I read the seminal book, “Nail It then Scale It” by Paul Ahlstrom and Nathan Furr. I realized I needed more robust validation. This led to cold-calling 100 potential customers and seeing if I could get a response. Thirty wanted to talk, and after about five months, seven became our first paying beta customers. This was a strong sales funnel for not even having any software to buy yet.

I hired an executive team and raised $1 million in seed funding.

Around that time, I went to lunch with a fellow entrepreneur who had been through a couple of startups. I was enthusiastic about the raise, our revenue, our team and the market opportunity. He asked me, “What are you going to do with the $1 million?”

“Move to a bigger office, hire more staff and drive sales while we continue building product,” was my response.

“You shouldn’t do that. You need to slow down,” he told me. “You need to make doubly sure you’re on the right path.”

But I liked nothing about “slow”. So we got to it and grew revenues to $2.8 million by the end of the second year. I thought we had nailed it, so we were eager to scale it.

I was wrong. I should have listened, but I had a fire in my belly — and what I thought was evidence I had done it the right way.

A year later, we were doing that first round of layoffs. Where did I go wrong?

Our initial target market was marketing teams for small software businesses. We had a strong, predictable funnel and were reaching our aggressive sales targets. The problem was not in our ability to sell; it was in our ability to deliver the value our software promised.

Demo automation worked well, but it depended on the customer creating demo video clips and documents to put into the platform. Surprisingly, marketers had little to no skills to do this. We hustled to build our own video creation team to help customers. Even this bogged down in endless review cycles. Some customers weren’t getting a single demo created in the first year. So, not surprisingly, when their annual contract came up for renewal, the chances of renewing were almost nil.

In hindsight, I should have worked through a small set of customers in a variety of segments over the course of a year and observed their behaviors. We should not have doubled down on sales and marketing until we knew we could reliably onboard, create value, renew and upsell that small group.

Failure #2: Product market unfit

The common adage about “product-market fit” is that “you’ll know it when you have it” or “When you have product-market fit, you’ll know because everything gets easier.”

These dubious business proverbs did prove to be true for me, but it was an arduous journey of pivot after pivot.

We had one midmarket customer, bigger than our other small business customers, that implemented Consensus across their sales team. They had instant success. This customer used no-frills screen recordings for their product demo content instead of high-production marketing animation videos. I soon decided we needed to go upmarket and no longer sell to small businesses.

I held a mock funeral for small businesses with my team to help them let go of the quick-fix crutch the SMB sales cycle had become. We would only target larger companies and begin selling into sales as well.

We still had a very high churn rate — about 40 percent. As much as we tried to educate them on creating screen recordings of product content, sales teams weren’t product experts and instead wanted to put their PowerPoint presentations into the platform. But buyers weren’t interested in slide decks. They wanted product knowledge.

Compared to the previous market of small-business marketers:

- (Unchanged) Enterprise sales teams did not have the know-how or the resources to implement effectively. Those few that did had very positive results, but most did not.

- (Unchanged) The sales tech space was noisy. While we had a unique offering, we were in the middle of an explosion of sales enablement technology.

- (Unchanged) They did not see the problem we were trying to solve as “mission critical.” They saw demo automation as a gimmicky way to get their slide decks in front of prospects.

- (Improved) They did not pay on time and were highly demanding of customer support, causing lower margins and cash flow concerns.

We still did not have product-market fit, and both churn and cash flow problems continued to dog us.

Upmarket sales engineers and product-market fit Nirvana

In 2017, a small team of sales engineers at Oracle purchased Consensus. They behaved differently than our other customers. They started building demo content videos even before the contract was signed. They were ready to launch on day one, started getting value immediately and required very little help from customer support. They purchased additional licenses in less than 90 days after launch, long before their first-year contract was up for renewal.

Intrigued, I began researching sales engineering in large software companies. We also set up a trip to visit the Oracle team in London. While onsite, trying to learn as much about them, their needs and why they purchased Consensus, they said, “We know you’re a small company. We want to help you all we can because we need to make sure you don’t go out of business. We searched for two years to find something like this. We NEED you!”

That was evidence they saw us as “mission critical.” As I researched this market, I could find little to no software designed and marketed to sales engineers. Could it really be possible that, with the billions of dollars put into marketing and sales tech, this critical area of the sales process had been completely overlooked?

We targeted and acquired a few more sales engineering teams as customers in both mid-market and enterprise companies. They all seemed to exhibit the same positive differences from the previous markets we had tried to address:

- Sales engineers saw demo automation as mission-critical to their success.

- They were usually already skilled at making product-centered content videos and documents needed to populate our platform and needed very little hand-holding.

- The “time-to-value” seemed to be less than 60 days.

- There were practically no competitors in this space.

- While these large customers often paid late, they always paid their bills.

In April 2019, I announced to our team that we were going to focus entirely on this market. We would stop selling into marketing and sales and sell exclusively to sales engineers.

My team choked on the idea. “85 percent of our customers are marketing,” my VP of client success said. “That’s where we’ve made our revenue.”

“But we’ve been losing ground in that market for the last three years,” I pointed out. “Our ARR is gradually shrinking. We’re in the land of the living dead at best.”

We made the change and launched our new website in June 2019. Leading indicators that it was the right move were almost instantaneous. Our lead flow tripled that month. I got deeply involved in the sales process, and conversations were electric. Their deep-seated need to solve the demo bottleneck inefficiencies was palpable.

Trailing indicators followed. Close rates increased. More importantly, most of these new customers were buying more licenses within the first six months. By the time their annual renewal came around, there was no question whether they would renew. Churn rates improved to less than 10 percent. For the first time in our history, we had a net revenue retention rate of over 100 percent (eventually getting as high as 141 percent).

We finally had the right market, but did we have the right product?

Failure #3: Not building flexibility into the initial product

As with most startup founders, I’m all about speed. That’s usually a strength, but sometimes it’s a weakness. A sign in one investor board room read, “You have to go slow to go fast.” At the time I saw that sign, I had no idea what it meant. “Go, go, GO!” was my modus operandi.

My focus on speed when building the initial product led to some early validation that was helpful but also forced me to make tradeoffs in the product. We’d build it on a deadline and fix it later.

Because of this, the initial product had very little flexibility to handle enterprise needs, such as hierarchical user and demo management, security layers and settings, and so on. Once we decided to focus on the large enterprise, I made a list of what was needed to meet their needs, took it to my CTO and asked, “How long will it take to retrofit these features onto our product?”

After analysis, he came back and said, “About 18 months.”

Shocked at how long it would take, I asked, “How long would it take to rebuild the entire platform from scratch with these features included?”

After a week or so, he came back and said, “About 18 months.”

It ended up taking two years, but rebuilding from scratch was essential to have the right product for the right market.

Everything got easier

Once we had the right product in the hands of the right market, the old adage came true: everything got easier. Leads flowed. Sales rates climbed. Retention and expansion are still the strongest in the industry. Customers rave. We now have over 700 five-star reviews on G2.

To achieve product-market fit, we ultimately had to make massive changes to our ideal customer profile as well as massive updates to the product itself.

Elon Musk famously said, “Starting a company is like staring into the abyss and eating glass.” I can relate to that. But once you have product-market fit, it’s also as rewarding as growing a garden with the perfect soil. When it’s not right, you work hard and get a few scrawny results. Once the soil is right, it’s not that you have to work any less, but all of your work yields a bounteous harvest.

The thing about success is that we usually quit before we reach it. We must persist long enough to outlast our failures.

A friend of mine, artist and entrepreneur Tim Paulson, often says, “Every painting looks like a failure halfway through.”

But what about once we reach that elusive success? Everything is always changing, and too many companies have tanked because they relied too much on previous successes and did not adapt to the future. As Rory Vaden famously said, “Success is never earned. It is rented. And rent is due every day.”