The road that led to Cartwheel started with math problems.

I am a classically trained mathematician. Solving math problems is what I had planned to do as a career. For years, I was keen on learning about high-dimensional geometry, but that only took me so far. As fun and interesting as it was to me personally, there were maybe three or four others in the world who cared about this specific problem the same way I did.

Fortunately, my course shifted: the skills I was developing transferred to artificial intelligence pretty well. It was called deep learning then, but it broadly contained the same concepts. To that end, I stopped pursuing my PhD to begin a role at OpenAI in 2021.

I had written a book that put me on their radar. I accepted a fixed-term visiting research position, and I worked on language models that wrote code. It was a real thrill to be a part of that, and I remain very proud of the work I did there.

At the same time, I was messing around with 3D animation software on the side. There were lots of opportunities to experiment beyond what I was working on. One piece of software I used was called Blender, which was open-source and free, so anyone could use it. More importantly, you could write code in it, and it would visually act out whatever you wrote code for.

Animating the future

There was a moment when I realized I had the most powerful tool for AI code, but I didn’t actually know how to use Blender. I wondered if I could connect the two so that Blender could be used to create motion and 3D modeling animation. I hooked it up, and it worked surprisingly well. It was doable. I thought, “Oh my goodness, this might be a paradigm shift in how we create art.” It was the same software that everyone else used, but it worked much faster.

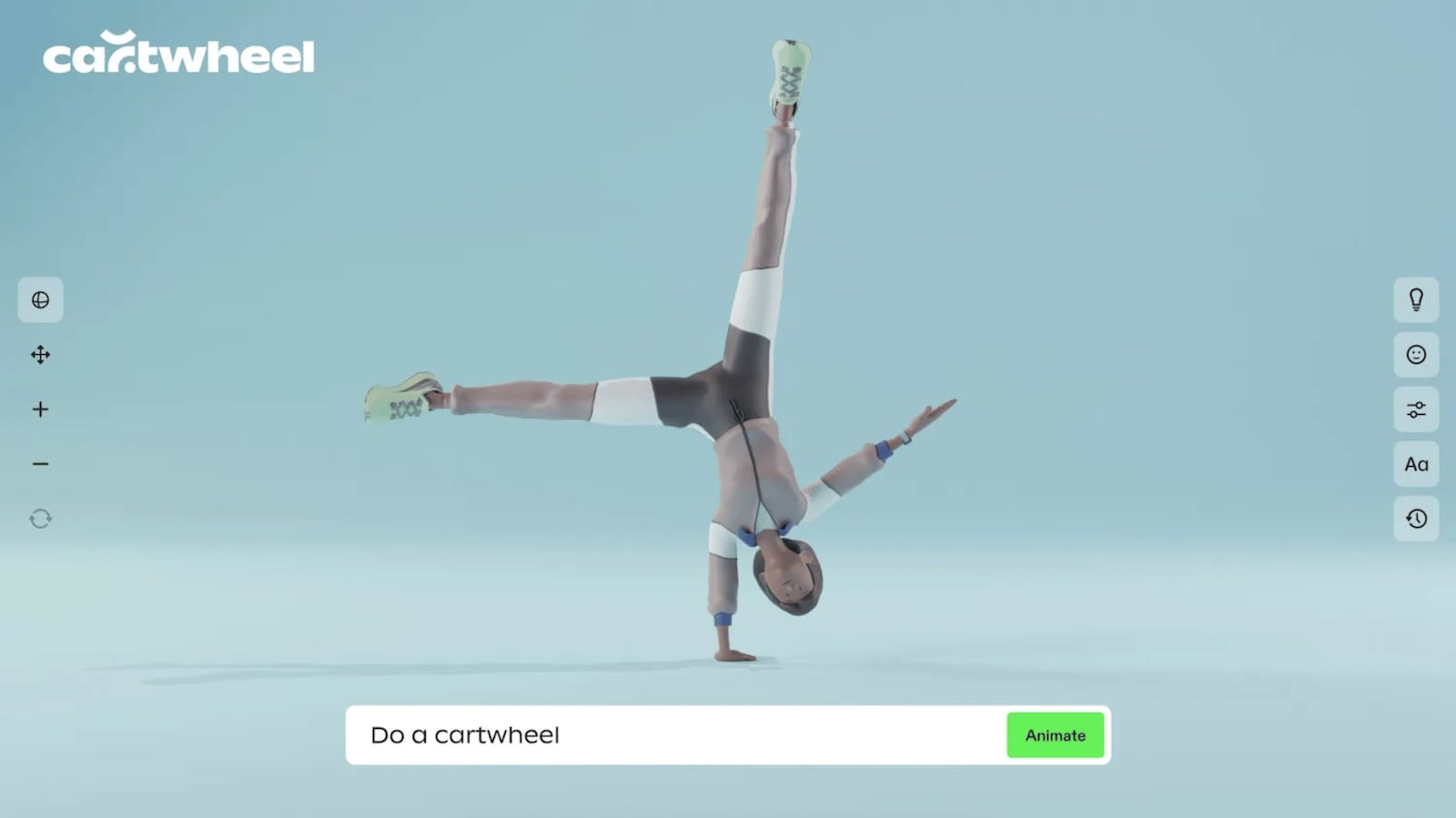

The general idea was this: You’d type in what you wanted your animation to do, and within 30 seconds or less, the characters you were using would act it out. More importantly, you weren’t using pixels but 3D characters and objects; if you were an animator, you could then download it directly into your software. From that point, you could tweak, edit, finesse, and do whatever you wanted to do because what you’d created was actually three-dimensional. The software allowed you to dramatically decrease the amount of time it usually took to generate animation while also significantly increasing its quality.

Every other Friday at OpenAI, we had the chance to present our completed work. If your creation was compelling enough, the company would organize a research team around it and develop it even further. I prepared a demo and presented it to the team. They agreed it was incredible, but they didn’t want to build it. They didn’t care about it quite that much.

On the other hand, however, I really did. A few days later, I was still thinking about it and realized the software was useful enough for me to keep moving forward with it. There was more to uncover, even though I didn’t know what it was exactly. All I knew was that it would be rooted in animation and the skills I’d been building already. When my fixed contract ended, I left to pursue this idea.

A few months into that journey, OpenAI reached out to me again. Someone who wanted to lead their design and product development had pitched them the same idea I had, nearly word for word. Apparently, he was more interested in doing what I was doing.

He got his chance. Jonathan Jarvis quickly became Cartwheel’s co-founder. I flew to New York City and met him, and it turned into a long chat that stretched over several months about what we would build together. After I showed him what I’d been working on, we resonated with this idea of making software that could be edited and speed up the process for artists. That’s how we would begin.

Landing on a name was one of our earliest decisions, and it was an easy one. When I was building the first prototype using stick figures, a cartwheel was the first motion that looked good. It was much less polished than what we have now, but when I typed in that I wanted my stick figure to perform a cartwheel, it actually looked like one. That was exciting for us.

Also, we were trying to turn the animation industry on its head. We wanted all we did to feel fun and playful, just like doing a cartwheel does. Animation only works how it’s supposed to work when you’re in that space.

After all the dust had settled, Cartwheel officially launched in 2023. This meant committing to the business full time, raising money and hiring a small team. After just over a year-and-a-half, we’ve made tremendous progress.

Enabling art in the age of AI

Motion data is new and is kind of its own category, which meant we had to create a new file format. Instead of using jpg or png for images, we have our own dot cartwheel file format. That’s a pretty hard computer science problem, but we dug our teeth into it and figured it out. The investment was worthwhile.

An even harder problem than that was hiring AI talent. We had a good team, but we’ve tried to hire people who have received $3 million deals elsewhere. That’s hard to compete with. One guy we were about to hire to work for us was offered twice his annual salary to stay in big tech.

With all the rapid advances being made in AI currently, there’s a huge talent war underway. Fortunately, my background is in AI. I understand what needs to be done and can do much of it myself. We trained all these models on our own hardware, which is still in my basement. I have graphics processing units (GPUs) running in what used to be a potato storage room, and that’s been really fun. What’s more, it’s saved us a lot of money.

It’s a little early to make any true projections, but the most likely scenario is that we fail, as most startups are prone to do. The second most likely scenario is that we get integrated into an existing product. For example, Snapchat may decide to animate their avatars more easily one day and buy us out to make that a reality.

Our true goal, though, is to continue making useful software that will exist for a very long time. Animation hasn’t changed since “Toy Story” — and that movie was made nearly 30 years ago. Tools and technology have remained largely the same ever since. We have an opportunity with AI technology to open the floodgates of animation to everyone, allowing them to tell and share great stories. People want to do that but haven’t had access.

We’re tasked with breaking the old Hollywood model. We break down existing distribution channels and enable people to make a living creating their art. Random people aren’t going to spend $10 million on an animated film. It’s up to us to bring that cost of creation down to zero.

For example, one episode of “The Simpsons” is 11 minutes long and costs $7 million to animate. “Frozen” was a great film — its budget was $150 million, and $80 million was earmarked for animation. As expensive as that is, animators don’t make a lot of money. By driving the cost to literally nothing, small animator teams can create longer, higher-quality shorts and films.

Charting Cartwheel’s future

We’re still a young company, so it’s hard to know if we’re succeeding or doing a great job. On the other hand, I think we’ll do great things. I’m hesitant to say anything confidently, but I think we’re on the right track. I think we’re building something cool. Early feedback tends to agree with me, and many people like it. We’ll keep trying to ride that and follow what the people want.

Cartwheel does have a compelling story, though, and that’s important. If you’re trying to raise capital, your biggest contributors are going to invest in the team and the story you’re telling. Investors don’t care about much else. As long as you can clearly communicate your ideas and back them up with your skillset, that’s a good place to be in.

In my opinion, what you shouldn’t do is start a company right out of school. You don’t have the network or honed skills you need yet. You don’t know what problems are actually hard. Finding actual problems you can solve requires you to work at other companies for a while. I’m 10 years into my career, and my co-founder has doubled that amount. We’ve been around the block, which helps inform a lot of the challenges we take on. We know what we’re likely to encounter and can avoid many of the more common pitfalls. Staying both small and lean means we haven’t spent a lot on headcount.

At Cartwheel, we’re making a creative tool — one that enhances what an artist does, not one that replaces them. It’s hard to communicate and position that. I want to live in a future where AI is a tool that people use to extend their capabilities, not where it is used to remove people from the equation. For a long time, I worked on AI that wrote code. It was my job. If I never had to write code ever again and AI could do it for me, I’d be happy, but I’m still always going to have to solve other problems. There’s so much more to do.

Math is (still) fun

Math is, in a sense, the universal descriptive language. It’s the precise way that you describe phenomena in the world. Code is the precise way that you get computers to do anything. Math and code are almost the same thing. To some degree, math is the way I get computers to do everything I want them to. It’s the ultimate tool in a lot of ways and is aesthetically very nice. The ideas are altogether pure, simple and utilitarian.

I’m lucky because Cartwheel still allows me to use math quite a bit. We do a lot of math with respect to motion. How things rotate in space is a geometry problem. How characters interact is an optimization problem. I still carry around a notebook that has nothing but math doodles in it. In that sense, my early esoteric interests are still paying off.

You may have no idea if there is an answer to a problem at first, but once you use math to find it, you know you have the tools you need to find the right answers. There’s little room for ambiguity there, and that’s comforting. Being able to solve issues so efficiently has a trickle-down effect when it comes to our customers. We get to pass that comfort onto them.